He was on his own for the first time. It was Rudo’s fourth birthday and all of a sudden he’s mature. As the sun raised on the dry southern savannah woodlands Rudo got up from his bed and started his day. He must have overslept because the rest of the herd seemed to have already gotten up to eat. “Shoot” Rudo thought “I knew I shouldn’t have slept for the entire 20 minutes. I’m so lazy”. Stretching to his tallest, 4.5 metres, Rudo looked around over the treetops to see if he could spot anyone else. But no one was there. He took a bit of leaves out of the acacia tree. How could he not see anyone, everyone knew that giraffes dominated the African landscape. He took another bite. No one; on his first day of being mature, on his 4th birthday, Rudo was left all alone in the African savannah.

“OW!” Rudo swung his head around. He felt another bite. “OW!” He swung his head the other way. “OW STOP IT!” Rudo shout out.

“Hold on a sec, you’re covered in ticks!” called out a little voice.

Rudo swung around “Who are you?”, “What are you doing on me”, “Ow stop pecking me!”, “Why am I so itchy?!”

Rudo felt the bird climb up all seven of his neck bones and to the top of his head, resting in between his two horns. The bird leaned over so Rudo could see him eye to eye. Rudo recognized the bird, he was an Oxpecker, and he had seen them on many other giraffes. It was a known fact that giraffes would provide these birds with protection and transportation if, in return, the birds would clear the giraffes of ticks. ‘That’s why I’m so itchy’ Rudo thought, ‘cause I’m covered in ticks… ew’. Rudo let the bird stay on and promised to take him across the river. In return, the bird would take care of his tick problem while he looked for other giraffes.

After a couple hours of walking and searching Rudo stopped. He couldn’t feel the bird’s pecking anymore. He wasn’t itchy anymore either. He looked around at his back, the Oxpecker was gone, and Rudo hadn’t even gotten him to his destination. What had happened to him? Rudo decided that he really didn’t have time to find out; he still had to find a herd. He decided that continuing his journey to the river would lead him to other animals that had maybe seen other giraffes.

As Rudo started to walk he noticed many small animals scurrying in the other direction. He lifted his feet to avoid them, only to smush some poor small creature in between his toes. Rudo felt so bad, he scraped the animal off of his foot and kept walking, forever mourning the death of the frightened animal. In the animal’s honour, Rudo vowed to find out what the newly deceased had been running from. He followed the trail of fleeing animals. It was leading him towards the river.

The closer to the river he got the larger the animals fleeing the scene were. All sorts of creatures were running away from what must have been the most terrifying event in Savannah history. Now Rudo was close enough to use his height to see what was going on without getting too close. Just as he suspected, the spotted hyenas were horrifying the few and suffering animals that couldn’t get away in time. Rudo contemplated standing up to the hyenas but quickly decided against it knowing that he had no business fighting them, especially since he would probably just end up wounded, or worse. Rudo wasn’t a fighter, and just like he ate the leaves of off the trees the hyenas needed to eat something, he just wished that that something wasn’t another living creature.

Now Rudo was really alone, all the animals had fled the river, the hyenas had caught and eaten their prey and not one animal remained. Rudo lifted his neck to pear across the landscape. He saw the most peculiar thing. An animal was it? It rolled across the dirt ground, over top bumps and rocks; it also created the most dust ever generated by an animal he had ever seen. As the animal got closer Rudo realized that inside this animal there were other animals. He didn’t understand. The animal seemed to be coming closer, so Rudo, curious as to what this animal was, stayed right where he was, he knew that this animal couldn’t hurt him. All of a sudden he felt something atop his head. The Oxpecker was back:

“Humans” Rudo heard the bird say. Rudo thought about it, he had heard of humans. Knowledgeable creatures he was told. They were also quite nice some of them, but others very cruel.

“Humans think they are all that with their fancy cars and cameras well ba humbug to them” and with that the bird flew away. The humans stopped the car right in front of Rudo. The dominant male spoke to the rest:

“This is a Giraffa camelopardalis, otherwise known as the giraffe” the crowd oohed and aahed, the male continued: “It was named Giraffa camelopardalis because it was once believed that the giraffe was a mix between camels and jaguars, we know that this is not true. It’s what we call a misnomer. This giraffe right here seems so be a male, about 4 years old–and rather smaller than the usual four year old male”.

Rudo was taken aback by this last comment ‘Sure I’m smaller, but you don’t have to point it out’ he thought. Even though the humans had ridiculed his height Rudo became rather attached to them, and after his last photo op he was slightly sad to see them drive off into the midday sun and leave him all alone again.

Rudo was just about to give up all hope when he heard a familiar slapping noise. His ears perked, he heard the shuffling of feet, the grunts of males. He heard them, he heard other giraffes! They were necking! When two males fight for dominance they swing their head and necks at each other until a winner can be named. Although Rudo, small and therefore weaker than most other males, didn’t like this ritual he would have gladly thrown himself at the other males for a chance to catch up with these other giraffes. Luckily giraffes are social and non-territorial creatures so they treated him as one of their own from the moment they saw him. Rudo even made a new lady friend. And he lived happily ever after.

More About Rudo

Rudo is a Giraffe! His scientific name is Giraffa camelopardalis. And his classification is:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Artiodactyla

- Family: Girrafidae

- Genus: Giraffa

- Species: Giraffa camelopardalis

General Description

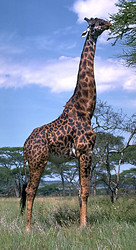

Giraffes are the world’s tallest land-living animal species. Although Rudo is quite short for his age, male giraffes are usually larger and heavier than females and can stand up to 5.5 metres tall, while females grow to be 4.3 metres. They have spots covering their entire bodies, except their underbellies, with each giraffe having a unique pattern of spots.

Characteristics

Giraffe eating. © 1999 California Academy of Sciences

Giraffa camelopardalis. © 2000 Greg and Marybeth Dimijian

One of the features giraffes are most known for are their long necks, which they use to browse the leaves of trees. They have seven vertebrae (just like humans) that are elongated.

A giraffe’s tongue can be up to 53 centimetres long. It is also prehensile, which means it can grab and hold onto objects.

The giraffes’ forelegs are longer than their hind legs. Giraffes have a distinctive walking gait, moving both right legs forward, then both left. At a gallop, however, the giraffe simultaneously swings the hind legs ahead of and outside the front legs, reaching speeds of 55 kilometres an hour. It cannot run for a long distance. Giraffes are a dangerous prey though, and when attacked the giraffe defends itself by kicking with great force. A single kick from an adult giraffe can shatter a lion’s skull or break its spine. Lions are the only predators which pose a serious threat to an adult giraffe.

Giraffes have small horns or knobs on top of their heads that are used to protect the head in fights. Both sexes have horns, although the horns of a female are smaller. The appearance of horns is a reliable method of identifying the gender of giraffes. Females have tufts of hair on top of the horns, whereas males’ horns are usually bald on top due to necking in combat.

Behaviour

Males often engage in necking, which is what Rudo saw when he found the other group of giraffes. It has various functions. One of its functions is combat. Battles can be fatal and the longer the neck, the greater the force a giraffe is able to deliver in a blow. Males that are successful in necking have great access to fertile females, so the length of the neck may influence sexual selection. Another function of necking is affectionate and sexual, in which two males will caress and court each other, leading up to sexual intercourse.

Giraffes are social animals. They travel in large herds that may consist of any combination of sexes or ages. Females tend to associate in groups of a dozen or so members, occasionally including a few younger males. Young males tend to live in bachelor herds and older males tend to lead more solitary lives.

Habitat

Rudo, like all Giraffes, lives in the dry savannah woodlands south of the Sahara in areas enriched with acacia growth. Giraffes are non-territorial and able to go long periods with no water, enabling them to venture away from a water source. Depending on food availability, giraffes can move up to 654 km (squared).

Adaptation to the Environment

- Giraffes are tall so they can reach leaves no other animal can, providing them with an untapped food source. They can also see danger from far away.

- Their skin coloring provides excellent camouflage in the African savannah woodlands.

- Their thick skin protects and insulates them from their often harsh surrounding.

- Giraffes’ long eyelids keep out ants and have the ability to sense thorns when looking for food.

- Special valves in the neck veins control the huge rush of blood to the head when the giraffe leans over.

- The giraffe has a “Wonder Net”, a network of capillaries in the brain acting as a shock absorber and preventing unconsciousness. It is especially useful during necking.

- They have extremely long tongues that can be up to 18 inches long and are used to reach leaves.

- The giraffe’s mouth is grooved so that it can easily strip leaves off of the branch.

- They have the ability to get water from food and retain it for long periods of time, so they can survive in dry areas where there are not a lot of water sources.

- Giraffes sleep for periods of 5-10 minutes lying down and rarely sleep for more than 20 minutes a day, protecting them from enemies and giving them plenty of time to eat.

Giraffes bending down to drink. © Patrick Giraud

Reproductive Characteristics

A male (bull) and his baby (calf). © Mila Zinkova

Giraffes reproduce sexually. Reproduction is polygamous, with a few older males impregnating all the fertile females in a herd. Male giraffes determine female fertility by tasting the female’s urine. Female giraffes typically give birth to one calf after a fourteen to fifteen-month gestation period. The mother gives birth standing up. At birth, the giraffe is about 1.8 metres tall and weighs between 45 and 68 kilograms. Within a few hours of being born, calves can run around but for the first two weeks they spend most of the time lying down.

During the first week of its life, the mother carefully guards her calf. Young giraffes are very vulnerable and cannot defend themselves. The young can fall prey to lions, leopards and hyenas. While mothers feed, the young are kept in small nursery groups. It takes about 3-5 years for a young giraffe to mature but only 25 to 50% of giraffe calves reach adulthood. That's why Rudo was so excited that he turned four: he was now finally mature! After 4-6 years they are sexually mature. The life expectancy is between 20 and 25 years in the wild and 28 in captivity.

Ecosystem

Giraffes play host to some troubling pests called ticks. To get rid of them giraffes take part in a symbiotic relationship with the Oxpecker birds, the kind of bird that Rudo traveled with. Giraffes provide security and transportation for the birds while the birds rest on the backs and necks of the giraffes, removing the ticks from the giraffe’s skin.

Conservation

Giraffes are hunted for their meat, coat and tails. The tail is prized for good luck bracelets, fly whisks and string for sewing beads. The coat is used for shield coverings. Habitat destruction and fragmentation are also threats to giraffe populations. The giraffe population is shrinking in West Africa but the populations in eastern and southern Africa are stable and, due to ranches and sanctuaries, expanding. The giraffe is a protected species. The total African giraffe population has been estimated to range from 110,000 to 150,000.

Information on the Internet

- Giraffe

- Giraffe - Kid's Planet Easy, clear website with the basic information about Giraffes.

- Mammals: Giraffe

- The Photography and Behaviour of Giraffes Clear information about the giraffe's behaviour and a lot of beautiful pictures.

- Giraffe - Wikipedia More difficult, longer website with detailed information and descriptions.

- Giraffe - MSN Encarta A lot of good information, but definitely more difficult than the other websites.

- Giraffe - MSN Encarta

- Oxpecker family

- Is the Oxpecker a conditional cleaner?

- Giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis, Fact Sheet 2003

- Mammals: Giraffe (San Diego Zoo) Fun and interesting website with tons of clearly arranged information.

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site