Oonopidae

goblin spiders

Wouter Fannes

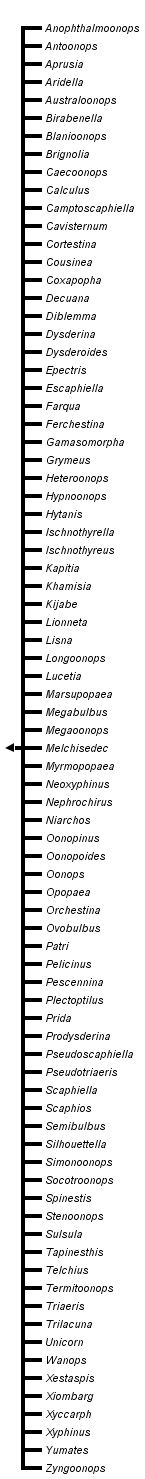

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

Oonopidae are very small (1-3 mm), free-living, haplogyne spiders. They occur throughout the temperate and tropical regions of the world, in habitats as diverse as deserts, savannahs, mangroves and rainforest (e.g. Grismado 2010, Jocqué and Dippenaar-Schoeman 2007). To date, more than 600 species have been described, making the Oonopidae the second-largest family in the Haplogynae (Platnick 2010).

Oonopids have adapted to a wide variety of ecological niches. Some species are ground-dwellers (Ubick 2005) while others are arboreal (Fannes et al. 2008) or cavernicolous (Harvey and Edward 2007). Still others live in ant nests (Jacobson 1933) or inside termite mounts (Benoit 1964).

The family has a rich fossil record that reaches back to the Cretaceous (Dunlop et al. 2010). Hitherto, more than 30 fossil species have been described, from various ambers (e.g. Baltic, Dominican, Lebanese, Chinese). Most fossil species have been placed in the extant genus Orchestina (Dunlop et al. 2010). More information on the palaeontology of oonopids can be found in Marusik and Wunderlich (2008) and Penney (2006).

Characteristics

Oonopidae are small, short-legged, mostly six-eyed spiders. They vary widely in carapace shape, eye arrangement, and degree of body sclerotisation. Some genera are soft-bodied (e.g. Orchestina) while others are heavily armoured (e.g. Opopaea, in which the abdomen is almost completely covered by sclerotized plates). Female genital morphology is highly variable within the family, with some species having ‘cul-de-sac’ spermathecae and others having entelegyne-type genitalia (e.g. Burger et al. 2003, Platnick and Dupérré 2009). Male palpal morphology also varies tremendously (see e.g. Saaristo 2001). Some oonopid genera have evolved truly bizarre pedipalps. In Ischnothyreus, for example, the male palp is completely sclerotized and appears pitch-black (e.g. Edward and Harvey 2009), while in Camptoscaphiella the palpal patellas have become hugely enlarged (e.g. Baehr and Ubick 2010). In other genera the males express peculiar somatic characters. For example, males of Unicorn have clypeal horns, and males of the genus Cavisternum are characterised by elongated cheliceral fangs and a strongly concave sternum (Baehr et al. 2010, Platnick and Brescovit 1995).

Biology

Little is known about the biology and natural history of oonopids. All species appear to be vagabonds that actively pursue their prey. They are thought to feed on mites and on small insects such as firebrats and collembolans (e.g. Parker 1991). There are some reports of oonopids being present near the webs of other, larger spiders, where they may act as scavengers of insect remains (Bristowe 1948, Knoflach et al. 2009). At least some species build delicate silk nests for resting and moulting (e.g. Knoflach et al. 2009).

The reproductive biology of oonopids has long remained poorly known, but in recent years a great deal of progress has been made (e.g. Burger 2009, Korenko et al. 2009). The mating biology of Orchestina and Silhouettella is particularly well-known (see Burger 2007, Burger et al. 2006, 2010). In these genera, females sometimes mate with multiple males. During second matings, females of Silhouettella often dump the sperm of the previous male; this may be an example of cryptic female choice (Burger 2007). The widespread oonopid Triaeris stenaspis may be an obligate asexually reproducing species. No males have ever been found (Platnick 2010), and laboratory studies have demonstrated that females can reproduce parthenogenetically (Korenko et al. 2009).

Oonopids tend to produce few, but large, eggs. Females of Triaeris stenaspis lay egg clutches composed of only two eggs, as do the females of Oonops pulcher and Oonops domesticus (Korenko et al. 2009, Knoflach et al. 2009 and references therein). The egg sacs of Cortestina thaleri contain only a single, very large egg (Knoflach et al. 2009). In some species females seem to guard their egg sacs (Knoflach et al. 2009). As with most small spiders, oonopids require only a few molts to reach maturity. T. stenaspis has been shown to pass through three juvenile instars (Korenko et al. 2009); in Cortestina postembryonic development also seems to involve three stages (Knoflach et al. 2009).

More information on oonopid biology can be found in Dippenaar-Schoeman and Jocqué (1997), Knoflach et al. (2009) and Ubick (2005).

Taxonomy

The family Oonopidae was established by Simon (1890, 1893) for a group of six-eyed, haplogyne spiders. Simon presented a detailed discussion of the biology and morphology of oonopids (Simon 1893), but, as was common in the nineteenth century, provided no formal diagnosis of the family. During the twentieth century a large number of new species and genera were added to the Oonopidae (e.g. Benoit 1964, Brignoli 1979) but the diagnostic characters of the family remained unclear (see e.g. discussion in Platnick and Brescovit 1995). Even today a clear, workable family diagnosis is still lacking.

In his classic work Histoire naturelle des araignées (1893) Simon divided the Oonopidae into two informal groups, the ‘Oonopidae molles’ (soft-bodied oonopids) and the ‘Oonopidae loricatae’ (armoured oonopids). In the subsequent literature, these two groups were sometimes treated as subfamilies and called the Oonopinae and Gamasomorphinae, respectively (e.g. Petrunkevitch 1923, Dumitresco and Georgesco 1983). However, the monophyly of these subfamilies is uncertain (Platnick 2000, Platnick and Dupérré 2010) and remains to be tested. In addition to the Oonopinae and Gamasomorphinae, two other subfamilies have been proposed, the monogeneric Orchestininae (Chamberlin and Ivie 1942) and the Pseudogamasomorphinae (Dumitresco and Georgesco 1983). Neither of these subfamilies has gained widespread support; indeed, most workers have ignored these taxonomic concepts.

More than 70 oonopid genera have hitherto been established (Platnick 2010). Unfortunately, many genera have been poorly described and inadequately illustrated. In addition, oonopid taxonomy has been plagued by lost or severely damaged holotypes (e.g. Australoonops), descriptions on the basis of juvenile specimens (e.g. Aprusia, Camptoscaphiella), inadequate diagnoses, and an overload of monotypic genera. All this has resulted in considerable taxonomic confusion (Ubick 2005). However, the situation is now rapidly improving (see e.g. Baehr and Ubick 2010, Platnick and Dupérré 2010). Crucial to this improvement has been the launch in 2006 of the Goblin Spider Planetary Biodiversity Inventory, an international research project that aims to produce a global taxonomic revision of the family. This project has generated a large number of revisions as well as descriptions of new taxa (see http://research.amnh.org/oonopidae/).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The Oonopidae are nested deeply within the Haplogynae (see Coddington 2008 for cladogram). They belong to the superfamily Dysderoidea and are the sister group of the Orsolobidae, a relatively small family with an austral distribution (Platnick et al. 1991, Ramírez 2000). Synapomorphies uniting the Oonopidae and Orsolobidae are 1) presence of only two tarsal claws, 2) claw dentition bipectinate, and 3) presence of proprioreceptor bristles on the tarsi (Forster and Platnick 1985, Platnick et al. 1991, Ramírez 2000).

The monophyly of the Oonopidae has not yet been adequately tested. Given the high morphological diversity within the family, a thorough cladistic test of oonopid monophyly is urgently needed. However, it should be noted that recent histological studies by Burger and Michalik seem to support oonopid monophyly. These authors examined the male reproductive system of several spider families, including oonopids, orsolobids and dysderids. They found that oonopids are unique among spiders in having completely fused testes, suggesting that the family is indeed a natural group (Burger and Michalik 2010, Michalik 2009).

The internal phylogeny of the Oonopidae is poorly understood. Comprehensive phylogenetic analyses have not yet been undertaken, and only few authors have discussed intrafamilial relationships. However, it has been argued convincingly that Orchestina, Unicorn, Xiombarg and Cortestina are the most primitive oonopid genera (Platnick and Dupérré 2010). These genera have a well-sclerotised sperm duct in the bulb and an H-shaped eye pattern, two characters also found in orsolobids (e.g. Forster and Platnick 1985).

Other Names for Oonopidae

- Vernacular Names: goblin spiders, dwarf hunting spiders, dwarf six-eyed spiders

References

Baehr, B.C., M.S. Harvey, and H.M. Smith. 2010. A review of the new endemic Australian goblin spider genus Cavisternum (Araneae: Oonopidae). American Museum Novitates 3684: 1–40.

Baehr, B.C., and D. Ubick. 2010. A review of the Asian goblin spider genus Camptoscaphiella (Araneae: Oonopidae). American Museum Novitates 3697: 1–65.

Benoit, P.L.G. 1964. La découverte d'Oonopidae anophthalmes dans des termitières africaines (Araneae). Revue de Zoologie et de Botanique Africaines 70: 174–187.

Brignoli, P.M. 1979. Ragni del Brasile V. Due nuovi generi e quattro nuove specie dello stato di Santa Catarina (Araneae). Revue Suisse de Zoologie 86: 913–924.

Bristowe, W.S. 1948. Notes on the structure and systematic position of oonopid spiders based on an examination of the British species. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 118: 878–891.

Burger, M. 2007. Sperm dumping in a haplogyne spider. Journal of Zoology 273: 74–81.

Burger, M. 2009. Female genitalia of goblin spiders (Arachnida: Araneae: Oonopidae): a morphological study with functional implications. Invertebrate Biology 128: 340–358.

Burger, M., W. Graber, P. Michalik, and C. Kropf. 2006. Silhouettella loricatula (Arachnida, Araneae, Oonopidae): a haplogyne spider with complex female genitalia. Journal of

Morphology 267: 663–677.

Burger, M., M. Izquierdo, and P. Carrera. 2010. Female genital morphology and mating behavior of Orchestina (Arachnida: Araneae: Oonopidae). Zoology 113: 100–109.

Burger, M., and P. Michalik. 2010. The male genital system of goblin spiders – Evidence for the monophyly of Oonopidae (Arachnida: Araneae). American Museum Novitates 3675: 1–13.

Burger, M., W. Nentwig, and C. Kropf. 2003. Complex genital structures indicate cryptic female choice in a haplogyne spider (Arachnida, Araneae, Oonopidae, Gamasomorphinae). Journal of Morphology 255: 80–93.

Chamberlin, R.V., and W. Ivie. 1942. A hundred new species of American spiders. Bulletin of the University of Utah 32(13): 1–117.

Coddington, J. 2008. Haplogynae. Version 19 August 2008 (temporary). http://tolweb.org/Haplogynae/2650/2008.08.19 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/.

Dippenaar-Schoeman, A.S., and R. Jocqué. 1997. African spiders: an identification manual. Plant Protection Res. Inst. Handbook, no. 9, Pretoria, 392 pp.

Dumitresco, M., and M. Georgesco. 1983. Sur les Oonopidae (Araneae) de Cuba. Résultats des Expéditions Biospéologiques Cubano-Roumaines à Cuba 4: 65–114.

Dunlop, J.A., D. Penney, and D. Jekel. 2010. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In Platnick, N.I. (ed.) The world spider catalog, version 11.0. American Museum of Natural History, online at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/index.html.

Edward, K.L., and M.S. Harvey. 2009. A new species of Ischnothyreus (Araneae: Oonopidae) from monsoon rainforest of northern Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum 25: 287–293.

Fannes, W., D. De Bakker, K. Loosveldt, and R. Jocqué. 2008. Estimating the diversity of arboreal oonopid spider assemblages (Araneae, Oonopidae) at Afrotropical sites. Journal of Arachnology 36: 322–330.

Forster, R.R., and N.I. Platnick. 1985. A review of the austral spider family Orsolobidae (Arachnida, Araneae), with notes on the superfamily Dysderoidea. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 181: 1–230.

Grismado, C.J. 2010. Description of Birabenella, a new genus of goblin spiders from Argentina and Chile (Araneae: Oonopidae). American Museum Novitates 3693: 1–21.

Harvey, M.S., and K.L. Edward. 2007. Three new species of cavernicolous goblin spiders (Araneae, Oonopidae) from Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum 24: 9–17.

Jacobson, E. 1933. Fauna Sumatrensis. Araneina. II. Biologischer Teil. Tijdschrift voor Entomologie 76: 398–400.

Jocqué, R., and A.S. Dippenaar-Schoeman. 2007. Spider families of the world. Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, 336 pp.

Knoflach, B., K. Pfaller, and F. Stauder. 2009. Cortestina thaleri - a new dwarf six-eyed spider from Austria and Italy (Araneae: Oonopidae: Oonopinae). Contributions to Natural History (Bern) 12: 743–771.

Korenko, S., J. Smerda, and S. Pekar. 2009. Life-history of the parthenogenetic oonopid spider, Triaeris stenaspis (Araneae: Oonopidae). European Journal of Entomology 106: 217-223.

Marusik, Y.M., and J. Wunderlich. 2008. A survey of fossil Oonopidae (Arachnida: Aranei). Arthropoda Selecta 17: 65–79.

Michalik, P. 2009. The male genital system of spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) with notes on the fine structure of seminal secretions. Contributions to Natural History (Bern) 12: 959–972.

Parker, J.R. 1991. The Oonops enigma. Newsletter of the British Arachnological Society 62: 1–2.

Penney, D. 2006. Fossil oonopid spiders in Cretaceous ambers from Canada and Myanmar. Palaeontology 49: 229–235.

Petrunkevitch, A. 1923. On families of spiders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 29: 145–180.

Platnick, N.I. 2000. On Coxapopha, a new genus of the spider family Oonopidae from Panama (Araneae Haplogynae). Memorie della Società Entomologica Italiana 78: 403–410.

Platnick, N.I. 2010. The world spider catalog, version 11.0. American Museum of Natural History, online at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/INTRO1.html.

Platnick, N.I., and A.D. Brescovit. 1995. On Unicorn, a new genus of the spider family Oonopidae (Araneae, Dysderoidea). American Museum Novitates 3152: 1–12.

Platnick, N.I., J.A. Coddington, R.R. Forster, and C.E. Griswold. 1991. Spinneret morphology and the phylogeny of haplogyne spiders (Araneae, Araneomorphae). American Museum Novitates 3016: 1–73.

Platnick, N.I., and N. Dupérré. 2009. The American goblin spiders of the new genus Escaphiella (Araneae, Oonopidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 328: 1–151.

Platnick, N.I., and N. Dupérré. 2010. The goblin spider genera Stenoonops and Australoonops (Araneae, Oonopidae), with notes on related taxa. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 340: 1–111.

Ramírez, M.J. 2000. Respiratory system morphology and the phylogeny of haplogyne spiders (Araneae, Araneomorphae). Journal of Arachnology 28: 149–157.

Saaristo, M.I. 2001. Dwarf hunting spiders or Oonopidae (Arachnida, Araneae) of the Seychelles. Insect Systematics and Evolution 32: 307–358.

Simon, E. 1890. Etudes arachnologiques. 22e Mémoire. XXXIV. Etude sur les arachnides de l’Yemen. Annales de la Société Entomologique de France (6)10: 77–124.

Simon, E. 1893. Histoire naturelle des araignées. Paris: Roret, 1: 257–488.

Ubick, D. 2005. Oonopidae. In D. Ubick, P. Paquin, P.E. Cushing, V. Roth (editors), Spiders of North America: an identification manual: 185–188. Keene (New Hampshire): American Arachnological Society.

Title Illustrations

About This Page

Work on the oonopid Tree of Life page was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation and BELSPO.

Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Wouter Fannes at

Page copyright © 2010

Page: Tree of Life

Oonopidae . goblin spiders.

Authored by

Wouter Fannes.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Oonopidae . goblin spiders.

Authored by

Wouter Fannes.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 23 December 2010

- Content changed 23 December 2010

Citing this page:

Fannes, Wouter. 2010. Oonopidae . goblin spiders. Version 23 December 2010. http://tolweb.org/Oonopidae_/2713/2010.12.23 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site